But when she came out from beneath the table, she discovered that her house was nothing more than a jumble of wood and debris. She was very sad because she had no money at all to rebuild her house or to buy a new one. “What am I going to do?” she cried. She sat on the remains of what was once her front doorstep and put her head into her hands. “Hello there,” a cheery voice said. The woman lifted her head to see a hairy ape-like creature standing in front of her. She shrieked and jumped. “Who are you?” she demanded. “I’m Big Foot,” the creature said with a goofy grin. The old woman lived near a forest and had heard talk from the townspeople about a wild female big foot, but she had never really believed in it herself. And if it did exist, she had always thought that she wanted absolutely nothing to do with it. She eyed Big Foot wearily. “I’m only called Big Foot because I’m working with a group of humans to find ways to have a big healing footprint on the Earth. We call ourselves the Big Foot Food Forest.” “How do you mean?” the woman asked. “Usually, humans leave behind a damaging footprint on the planet. They burn fossil fuels, like coal and gasoline, clear forests, and manufacture cement, all of which releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. But it’s also possible to leave behind a healing footprint by regenerating the forests and the fields, and sequestering carbon back into the soil, where it belongs.” She thought this creature sounded otherworldly, and maybe even too smart for her own good. Like most townspeople, the woman was a bit superstitious, and didn’t trust newfangled ideas and theories like this. “Okay,” she said. “But why is it bad to have carbon in the atmosphere?” “Well because it contributes to climate change, which has other catastrophic effects like hotter temperatures, severe storms, increased drought, rising ocean levels, species loss, food scarcity, poverty and displacement.” “Hmph,” the woman said. “And did you know that one of the ways we can leave a restorative footprint is by building you a brand-new house out of straw bales?” “Now why would anyone want to build me a house? And out of straw bales?!” she said. “I think I heard of someone down yonder in Nebraska building a house from straw bales—wasn’t it eaten by a cow?” Big Foot laughed and sat down on a nearby tree stump. “Yes, yes, you’re right,” she said. “That did happen once, but only because they didn’t plaster the walls. Let me explain.” The woman gave Big Foot a shrewd, cold look. “Straw bales are made from the stalks of grain crops—wheat, oats, barley. It’s the stuff left over after the grain has been harvested. Since straw is considered a waste product, farmers usually burn it, which releases carbon into the air.” “Mmhm,” the woman said. “People have realised that instead of burning them, we can use the straw bales to build houses, which also sequesters carbon back into the bales! And since they’re considered a waste product, you can find them for very cheap. Plus, straw is non-toxic, so you know that your home is healthy and that you’re breathing clean air.” “Okay, fine, so it’s affordable, natural, yada, yada, yada,” the woman said. “But how does it work?” “You simply build a foundation and timber-frame, like most houses, then you stack rows of bales, which serves as the insulation. Finally, you plaster both sides of the straw bale wall with a formula of natural materials, like earth or clay.” “That’s it?” she said. “Surely it’s not safe then. I mean isn’t straw weak, flammable and prone to pests, rot and fungus?”

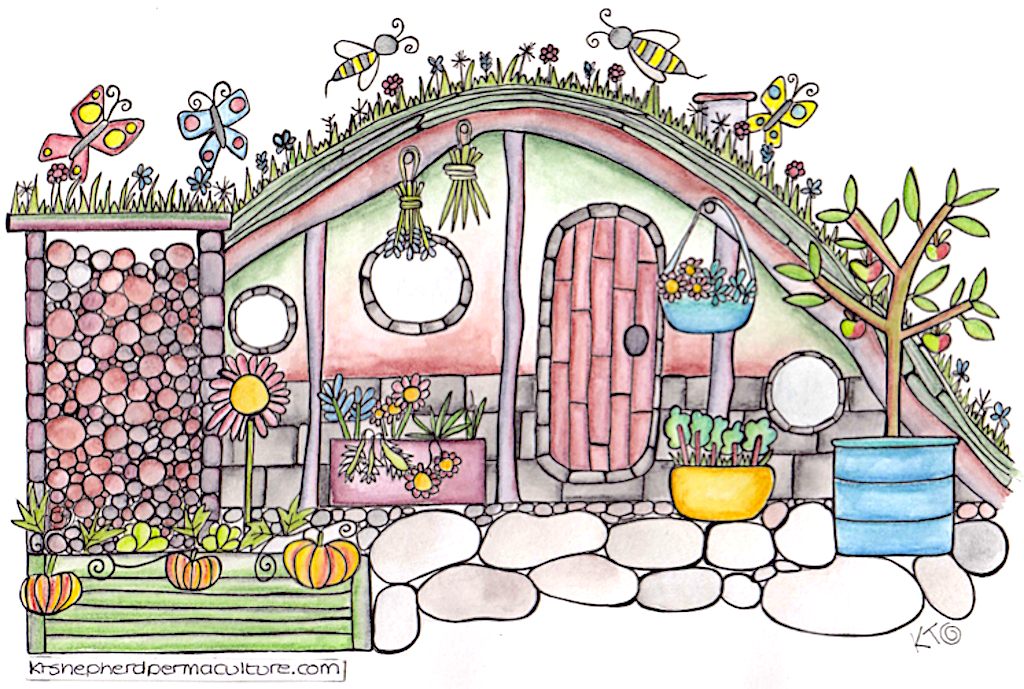

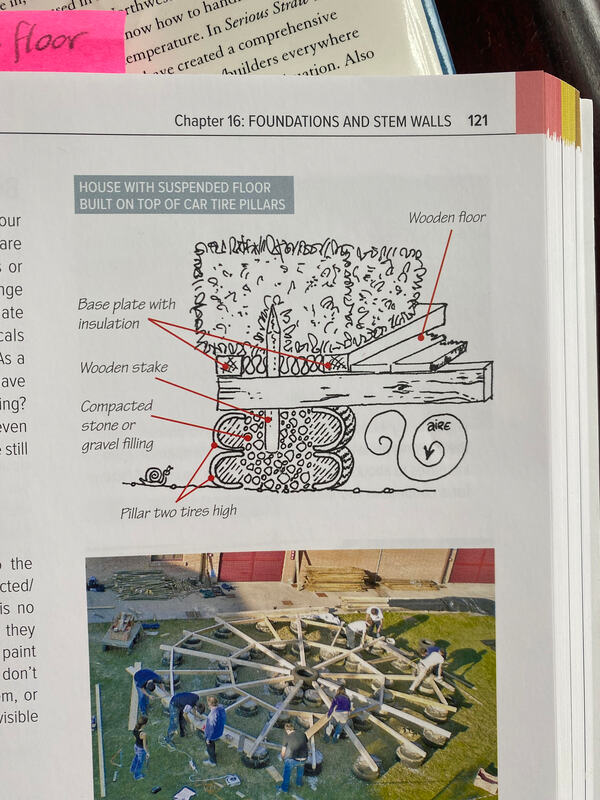

“Nope. Straw bales are very dense and strong—a single bale can weigh up to 45 pounds! And since they’re so tightly packed, they have three times the fire resistance of conventionally built walls. Pests are only a problem if they manage to sneak in during the construction process, which is why you must gather a. group of people to help build swiftly. Also, pests are more attracted to moist bales with high levels of grain residue, so you just need to avoid those two things. That’s why we build the house during a dry week in the summer. If the plaster coating is sealed properly, a straw bale house shouldn’t have any more problems with pests or moisture than the average house.” “But how do I know the house is going to last? I thought my wood house would stand forever and look at it now!” The woman turned to the mess of her former home—smashed windows, cracked beams and other detritus. “People have been building with straw for thousands of years—since the Paleolithic Era. Straw was used in construction in Germany, northern Europe, and Asia. Native Americans also used straw between the inner lining and outer cover of their teepees. More recently, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pioneers in Nebraska built houses, farm buildings, churches, schools, offices and grocery stores with straw bales. In addition, there are tons of new straw bale buildings constructed in the past thirty years all over the world: a seven-story housing project in France, public buildings in the U.K., and wineries, and office buildings in the USA. Many of these buildings have lasted for a hundred years already!” The woman squinted her eyes at Big Foot. She wasn’t easily convinced. “If you don’t believe me, you can check out this research from the University of Bath. They found that straw bale buildings offer higher levels of thermal insulation and regulation of humidity levels.” “But what if another earthquake hits?” “Gee, you’re right—that’s probably at the top of your list of concerns. I should’ve mentioned it earlier! Due to their flexible and springy nature, straw bales are ideal for seismic areas. Tests show that straw bale houses have a strong resistance to earthquakes, so you won’t have to worry about that again!” “If it’s so great, then why aren’t more people doing this?” “That’s a very good question,” Big Foot said. “It’s mostly because people get stuck in their ways. Also, unlike conventional materials, straw can’t be patented or profited from. Since it’s a waste product, it has no commercial value.” “Well, Big Foot, it all sounds fine and dandy,” the woman said. “But so far, you’ve only told me about the walls. You know that houses need floors and roofs too, right? What about those, huh?” “Yes, well, there are many types of naturally constructed floors and roofs, but we at Big Foot Food Forest use a modified version of the traditional Scandinavian-style sod roof and a method of earthen flooring. First, let me tell you about the sod roof!” The woman nodded uncertainly. “We’re going to line the roof with a rubber pond material called EPDM. Then we’re going to cut thick slabs of sod—blocks of grass from a field—and put them up on the roof. This way, the plants are already established in the soil and it’s free! This is how Scandinavian people have been doing it for thousands of years—only difference is that they used birchbark as the lining instead of EPDM.” “And these roofs, uh, work properly?” “Yeah! They act as natural insulators, which lowers your electricity bills, and if you use proper waterproofing techniques—with the EPDM—the maintenance is minimal! Not to mention, these roofs are very picturesque and attract lots of visitors.” “Huh,” she said. “Interesting. And what about the floors?” “We’re going to fill recycled car tires with stones and gravel to serve as the foundation under the straw walls. Old tires are usually thrown into landfills, where they degrade and leech into the earth. Instead, we can take advantage of the tires, which are usually free, to build. They’re virtually indestructible and since they’re flexible, they’re also resistant to earthquakes.” “Well, Big Foot, I think you got yourself a deal,” the woman said. “But don’t make me regret this!” The Big Foot Food Forest volunteers all pitched in some money to purchase the building materials, and they planned a day in April to gather and put in the foundation. Then they gathered again in May to have a frame-raising party. The old woman was surprised to see so many familiar faces in the crowd. She had no idea that so many of her neighbors also cared so much about the environment! If only she hadn’t been so nasty to them, she thought, maybe they could’ve gotten to know each other sooner. In June, the volunteers decided to get together for a whole week to build the walls. The first day of the wall-building was beautiful and warm with a gentle breeze. After the earthquake and the long, frigid winter, the relief of summer was palpable. Everyone happily worked together to raise the frame of the woman’s future home. They broke a sweat and felt strong and fulfilled as they used their muscles to lift the bales. Then in the evening, after they had finished, they ate a delicious dinner. Lastly, a few people played some music—guitars, banjoes, fiddles—while they roasted marshmallows around the campfire. The woman warmed her feet by the fire and looked up at the stars in the sky. She wondered if the earthquake had been a blessing in disguise because it had brought her to Big Foot Food Forest. The rest of the week it was not supposed to rain and they worked together to build the widow a new house. Big Foot taught them how to build floors from crushed sand, clay and straw bits, stack the bales in a running bond, and make a sod roof. Everyone had an important role to play in the endeavor. The strong people did most of the physical labor, while others prepared lunch and mixed the plaster recipe. Even in her old age, the woman felt welcome and useful. Even though she couldn’t lift the heavy bales, she could help by taking care of the little ones running around. She had forgotten how much she loved being around the joy of curious, smiling children. The week flew by and before they knew it, the house was done. The woman walked through her new home and her eyes watered. It was everything she had always dreamt of. She had always wanted a deep window seat in her house—a place where she could bask in the sun—however, she had assumed such a thing would be too difficult and too expensive to build. With straw, though, it had been simple—you just stacked the flexible bales and cut them, like a sculpture, into the shape you wanted. The woman’s new house also had embedded shelves, rounded corners and doors, and thick walls that kept her warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer. The thick walls made her feel very cozy, snug, and safe. The earth plaster finish of the walls also had a nice natural texture and tone that reflected the light streaming in from the large, rounded windows. The roof was beautiful with its vibrant, lively green, like something from a storybook. Over the years, people came to visit the woman all the time, dropping in to chat over a cup of tea and ask her about her lovely, handmade house. Occasionally, these people who visited were grumpy and dead set on proving her wrong. This, however, only made the woman smile knowingly. She remembered when she had been like that. Now, though, she had become the one who was patiently explaining and helping others to change their footprint from a damaging one to a big healing one. The woman was no longer cynical, lonely, or unhappy. Her heart was as full and vibrant as the green roof above her head, and she lived happily ever after in her straw bale house. Written by Jacqueline Knirnschild and Annababette Wils To learn more about straw bale building, we recommend the book, A Complete Guide to Straw Bale Building by Rikki Nitzkin and Maren Termens. Comments are closed.

|