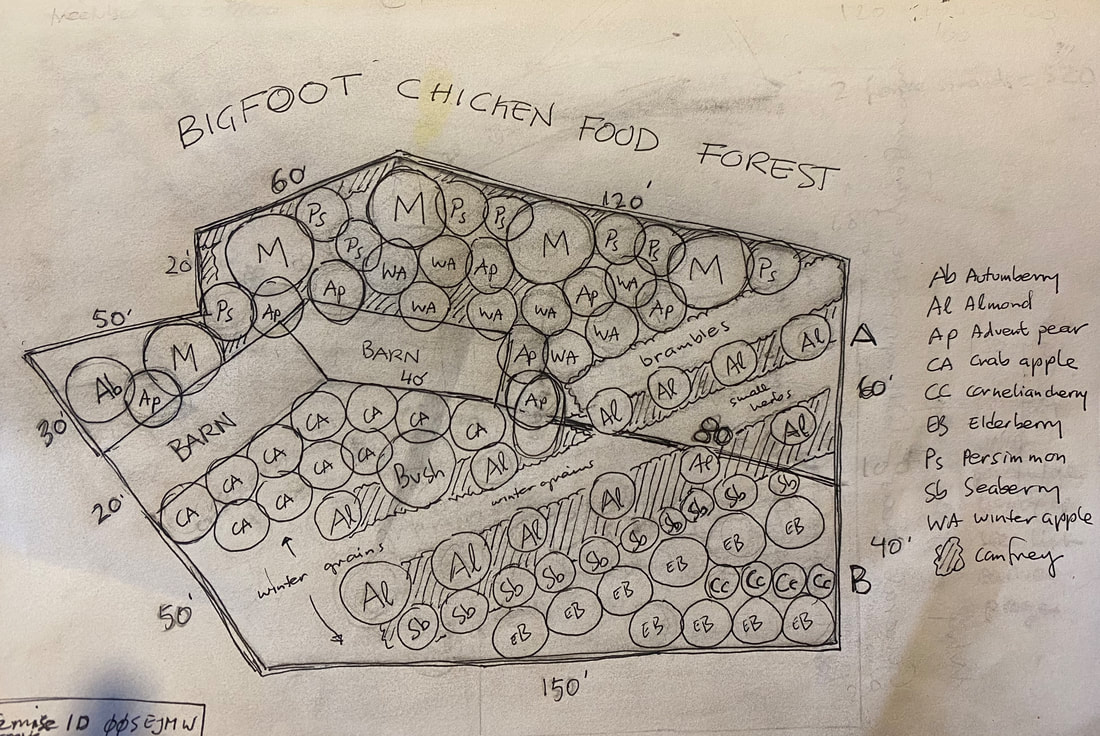

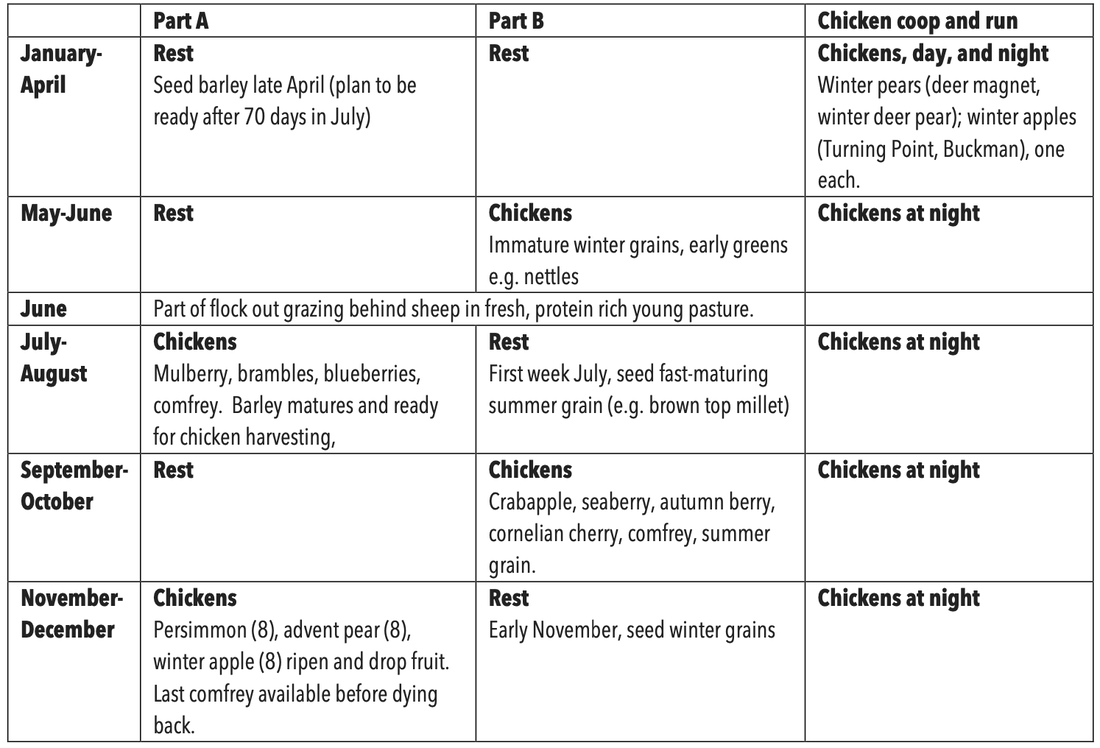

Babette’s favorite activity: making dream images. Here is a dream image of the chicken food forest. A thicket of shrubs laden with berries and an overstory of fruiting trees, dropping pears, persimmons, mulberries at different times of year. Chickens scratching the ground for the fallen fruit and hopping on branches to pick fruit themselves. Some areas with dense green undergrowth like comfrey and other herbs, but also mulchy areas under the trees breeding tasty little bugs. Lots of contented cackling and clucking. Chicken owner managing the forest but definitely not spending a lot of time on it once established. Hopefully chickens still laying their eggs in their nest boxes! Our dream chicken food forest is full of perennials. One of the first plants to enter the chicken food forest design was the perennial comfrey. Comfrey is an awesome chicken plant. For one, it has very high-protein leaves (over 20%) - in fact, it can adequately supply chickens with protein, an odd idea. A permaculture blogger who has inspired me in many ways, Sean Dembrowsky, has a couple of videos about feeding comfrey to his chickens. Another great characteristic of comfrey is its rapid growth – you can cut it to the ground multiple times in one season and feed all those leaves to your chickens. You could possibly feed a summer flock just on comfrey. Sean Dembrowsky cuts the comfrey and brings it to the chickens in a big wheelbarrow. But I wouldn’t mind if the chickens harvested it themselves. There is a problem though. If the chickens have access to the comfrey, how does it have a chance to regrow? I mulled this over for a while, and from this mulling came the idea of splitting the chicken food forest into two parts. Chickens spend time in part A eating all the comfrey to the ground; meanwhile comfrey in part B grows tall and lush. Next we move chickens to part B for a couple of months, and now the comfrey in part A can recover and regrow. Then the chickens move back to part A. Comfrey can be cut back to the ground up to five times per season, so two months should be ample time to grow back. The next plants to enter the chicken food forest design were fruiting bushes and trees, ideally a mix with a long fruiting season. I scoured my permaculture books, chicken books, the internet and came up with a pretty good list that included the following: June fruits - juneberry and haskap; July and August fruits - mulberry, brambles, elderberry, blueberry; September and October fruits - crabapple and other apple, seaberry, autumn berry; and there are even very late fruits for November and December – persimmon, advent pear, and winter apples. With the chickens see-sawing between parts A and B of the food forest, the fruits will be arranged across the two parts in such a way that they ripen when the chickens are there to harvest them. I ended up with the following two-month system: mulberries, brambles and blueberries in part A for July and August; crabapple, seaberry, and autumn berry in part B for September and October; persimmon, advent pear and winter apple in part A for November and December. I decided to skip June-bearing berries for now. A problem with the chickens’ scratching and eating of greenery, is that it might be difficult to get small trees and shrubs established. Once the shrubs and trees are bigger, the chickens will leave the hardened stems alone and focus on leaves and on fruits as they ripen. A solution proposed by Sean Dembrowsky is to put rocks around little seedlings. Genius. He also puts sticks around the seedlings so that the chickens have a harder time eating all the leaves (a plant is always happy to donate some of its leaves). Another fun thing we can do with the see-saw method is grow some worms. If there is a compost pile where the chickens are, the chickens eat the baby worms so they can’t get big and tasty. But if we have two compost piles, one in part A and one in part B, the worms and bugs and worms have two months at a time to grow chicken-free. Say the chickens start in part B in May and June. We feed the compost pile in part A and get some early worm growth. On chicken moving day at the end of June, we take some good shovel-full of compost A, hopefully with a fair number of worm eggs and worms of all ages, and inoculate compost pile B. In July and August, the chickens are in part A and scratch through compost there. Meanwhile, in compost B, worms and bugs are growing undisturbed for two months while we add new compost to the pile. End of August is moving day again. We inoculate compost A with a shovelful from compost B, and move the chickens to part B. I’m not sure if this cycle is too short – worms need about 6 weeks to hatch and 8 weeks to mature. It will be an experiment (another favorite Babette activity). This design so far leaves six months with no food in the chicken food forest. I decided it might be worth trying some winter grains, sown in part B in November. They would start to come up in March and by May, they would be tall and full of nutrients for the chickens to eat – even if not ripe with grain. Nettles and other early greens that come up in April before the chickens come out, could also provide eating in May and June. That would get us up to eight months, not too bad. The rest of the time, January – April, the chickens will be in their barn and run. Maybe we can get a couple of late winter bearing apples and pears going in the barn?... I measured out how much area we could devote to the chicken food forest, given that there are already so many other things planted – and found an area of around 1/3 of an acre around their barns. This was much less than the acre I had envisioned, but we can still make good use of it. A potential problem with this size of chicken food forest is over-nitrification. Chickens poop lots of nitrogen-dense packets, and these packets are one of the reasons that chicken yards tends to be fields of Mordor-like desolation. The soil just has too much nitrogen for plants to grow in it. According to people who have experimented with this, you can have up to 100 chickens per acre, but we will have 100 chickens on 1/3 acre. In the next letter, we think about how to address this problem. Putting it all together, here is a drawing of the design. The barn and chicken run, which will house the chickens at night and contain their egg boxes, goes through the middle of the chicken food forest. Part A is in the northern half because it will contain the tallest trees – the mulberries and persimmons. Part B goes along the bottom of the barn and run and makes up the southern half of the food forest. The design does not include a lot of detail on herbs and ground cover, except for the comfrey and the winter grains, but that will come by and by. I also added sowing of grains to the design – another experiment. Below is a table that shows the see-saw and what’s happening in each half of the chicken food forest as well as the chicken barn-run by season. If nothing else, this is sure to be an interesting experiment where we make lots of mistakes and we learn a lot about what to do and what not to do when you raise chickens in a natural system. :)

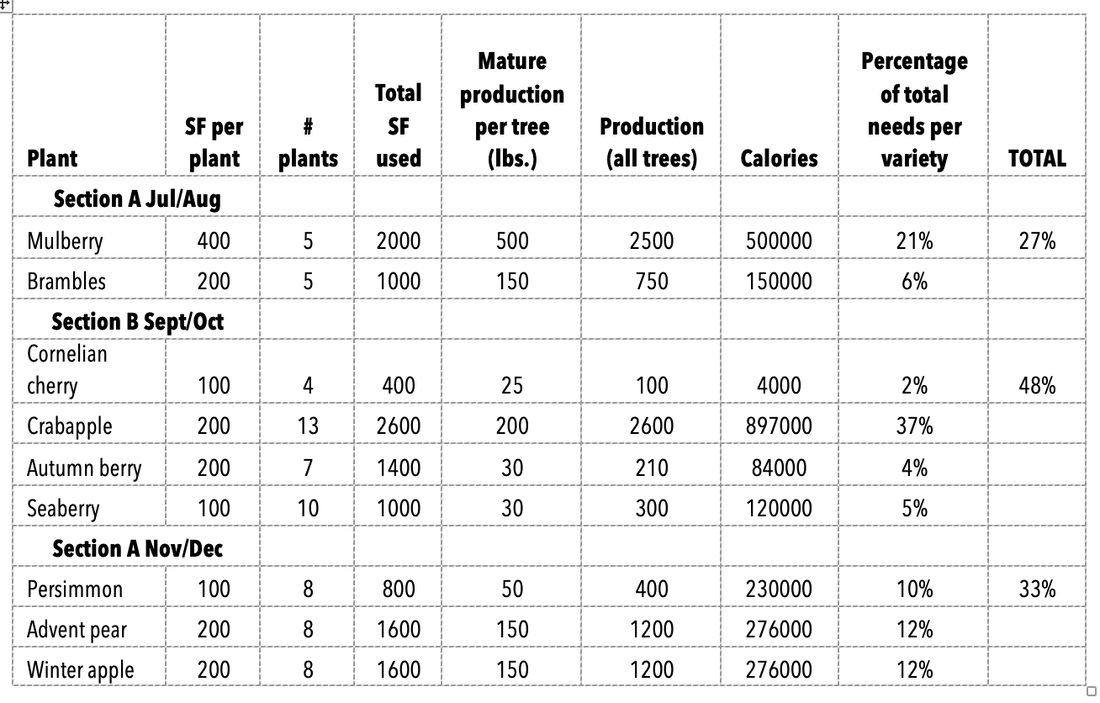

Being an optimist, I computed how much food this food forest is going to produce. I computed how many pounds we could expect from the fruit trees, the bushes, and the brambles, and estimated how many calories would be in that. This gives a high end of what the food forest might produce (although it does exclude grubs and worms, which will certainly also be around). I then used those numbers to give an optimistic estimate of how much of their food intake the chickens might get from the chicken food forest during each rotation. I figure that each hen needs about 400 calories per day, so for 100 hens during a 60-day rotation period, the total calorie requirement is 2.4 million calories. The bottom table shows how many fruit trees and shrubs we'll plant, the production per species of fruits, and the percentage of the 2.4 million calories. The table does not include calories and nutrients from comfrey, other ground cover plants, or soil grubs, but, on the other hand, the fruit estimates are optimistic, so maybe on balance the table is a reasonable guestimate of how much the food forest might cover chicken food needs in a given time period. It looks like the greatest coverage is in section B in September/October (48%), with lower rates in section A in July/August (27%) and November/December (33%). Mulberries and crabapples come out as champion feeders.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Babette WIlsBabette is a permaculture farmer in Western Massachusetts. She and people who are working with her on the farm are experimenting and learning on the go. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesHappy 2024!It’s 2024 and we are excited for this coming year. Lots of plans: integrating trees and livestock in silvopasture; working with other farmers in the area to promote agroforestry and make it a viable farming option; expanding our berry patches; and of course continuing our offerings at the Greenfield and Turners Falls farmers markets with our partner Just Roots!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed